Finally, sophisticated new computational tools are giving us an ever-clearer picture of the subtle information available in the child's environment 7, 8, and allowing us to implement, explore, and test complex theories of how learning works 8, 9. These advances are being supported by data from new technologies like eye-tracking and wearable cameras 6. There are new theoretical developments like a radical new understanding of learning (see Aslin article in this collection) as well as a richer understanding of how toddlers' own bodies play a role in cognition (see Oudeyer article in this volume and 5). The field of word learning is in the middle of a shift in viewpoint. Such knowledge is captured as constraints 2, principles 3, or more recently, prior expectations 4, and there is considerable evidence that children at some ages behave in ways that appear consistent with these kind of language specific abilities. For example, children may come to the word learning table with the assumption that most new words refer to whole objects (the rabbit) not parts (ears) or features (fluffy) or they may assume that words refer to the more common or “basic level” of description (e.g., gavagai means “rabbit”), rather than a subordinate level of description (e.g., “eastern cottontail rabbit” or “Peter rabbit”) or a superordinate level of description (e.g., “rodents”, “mammals”). How can children learn so many words so quickly?įor many years, the most widely-accepted answer to this question was that young learners are imbued with specialized abilities and/or innate knowledge that guide them to the correct word meanings. When the challenging problem of inferring a new word's meaning meets the poor cognitive skills of typical children, this creates a mystery. This problem is further complicated by the relative cognitive immaturity of the very young learner: toddlers have a limited understanding of abstract concepts they can't do math they can't hop on one foot and they are still learning to feed themselves.

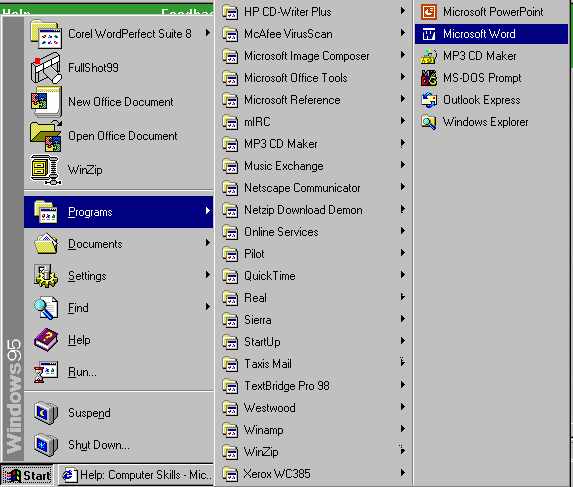

Cannot open wordfast classic on word 2000 how to#

One of the tribesmen shouts “gavagai.” How to you determine what this new word means? It could be “rabbit” but it could also be “hopping,” “fluffy,” “dinner,” “get it!” or a host of other things. You go hunting with a group of tribesmen and see a rabbit hop past. Imagine you are a field linguist studying a community whose language you do not know. illustrated the difficulty of this feat, which we paraphrase here: To reach an average-sized vocabulary by kindergarten, children have been argued to learn up to nine new words a day. Virtually everyone agrees that children's ability for language is amazing.

This research illustrates a core issue in the cognitive sciences: Is human language acquired via specialized mechanisms - or does it derive from more general developmental mechanisms that may be seen in other domains (like vision) and even in other species that lack language? This question has engendered an enormous amount of research over the last 40 years. How is this complex set of information learned? In the lexicon (our mental storehouse of words), these sequences must be linked to a rich set of semantic features, to syntactic properties like part of speech, and to other representations like orthography (the word's spelling). The spoken form of a word is a complex sequence of articulations and acoustic cues. Words are deceptively simple, but profoundly important to language.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)